by WCS Mesoamerica and the Caribbean; Analysis and graphics by Víctor Hugo Ramos and Jeremy Radachowsky. Text by Napoleón Morazán (WCS Honduras-Nicaragua), Boris Arévalo (WCS Belize) and Claudia Novelo Alpuche (WCS).

I. Global overview

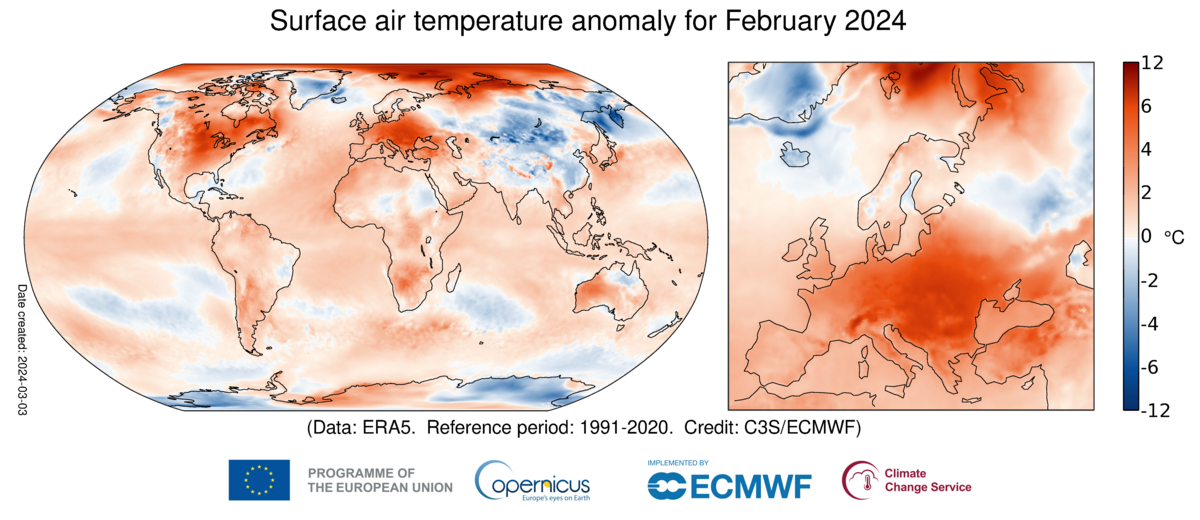

The Copernicus Climate Change Service recently published its climate bulletin for February 2024, with data on global surface air temperatures. This was the warmest February on record globally, 1.77°C warmer than the pre-industrial average temperature for this month, 0.81°C above the 1991-2020 average, and 0.12°C above the previous warmest February, in 2016.

However, the seasonal forecast indicates that the phenomenon has reached its peak and will continue to decrease during the forecast period, mid-year.

II. What is the forecast for Mesoamerica and its Great Forests this season?

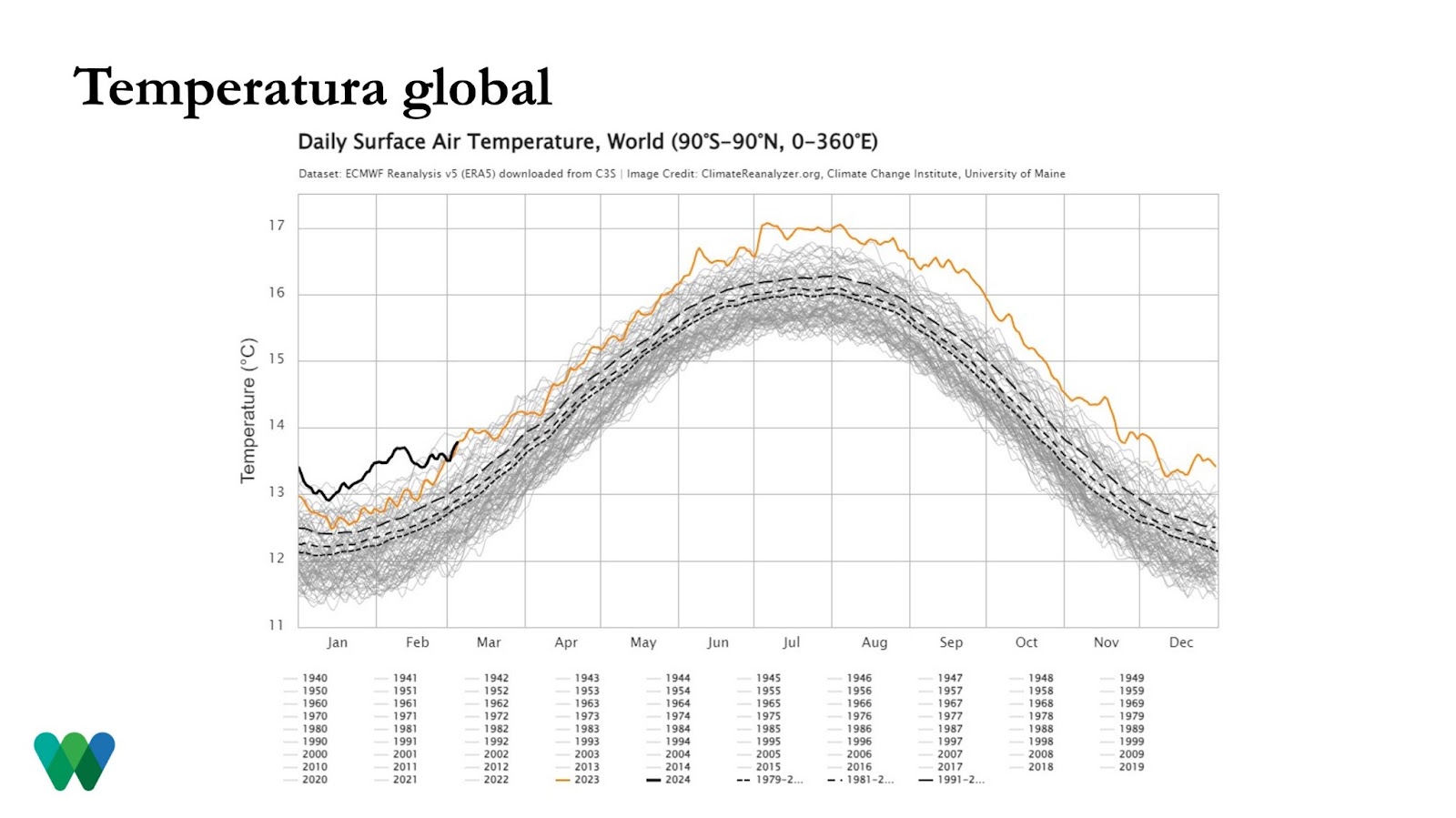

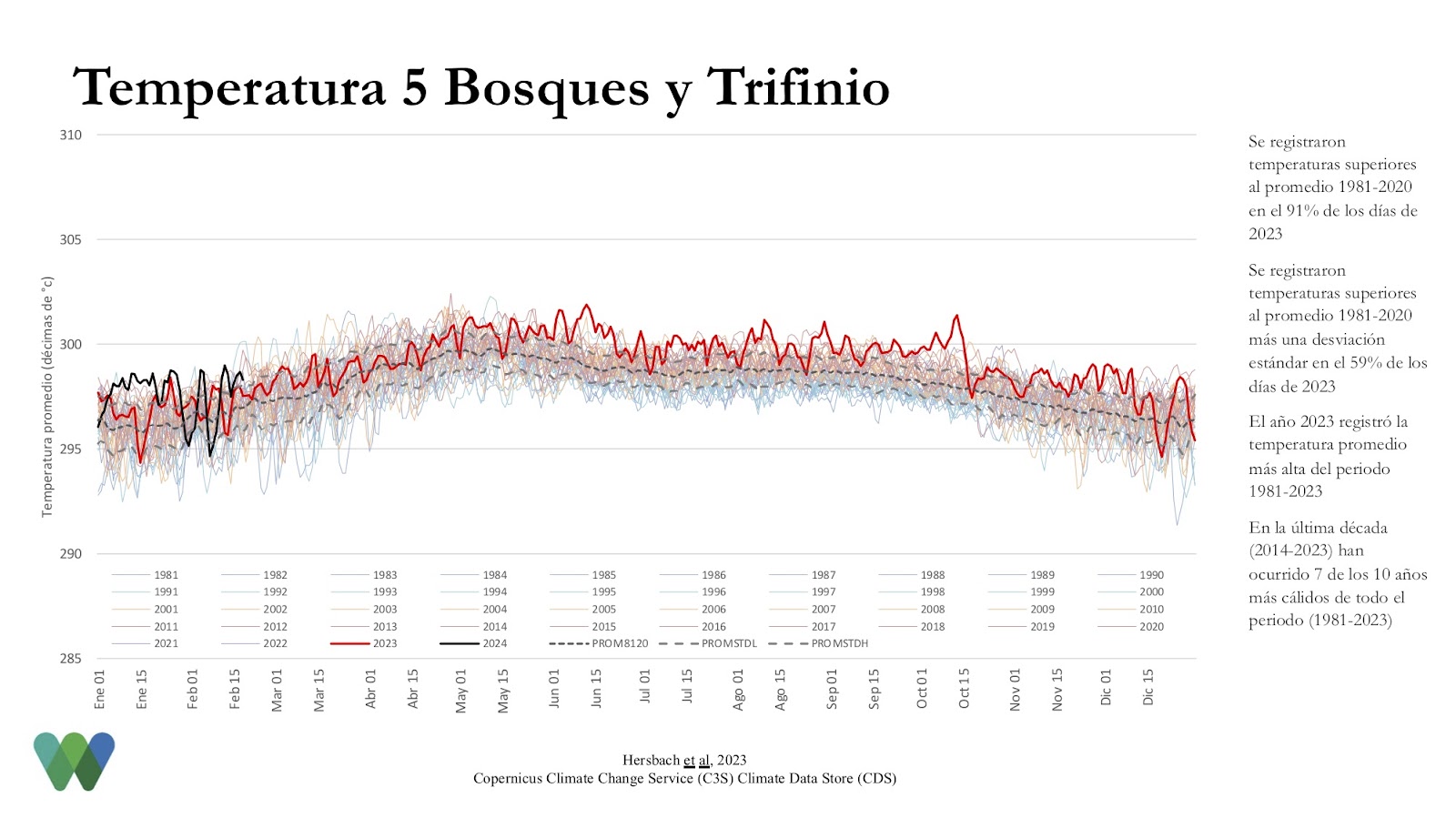

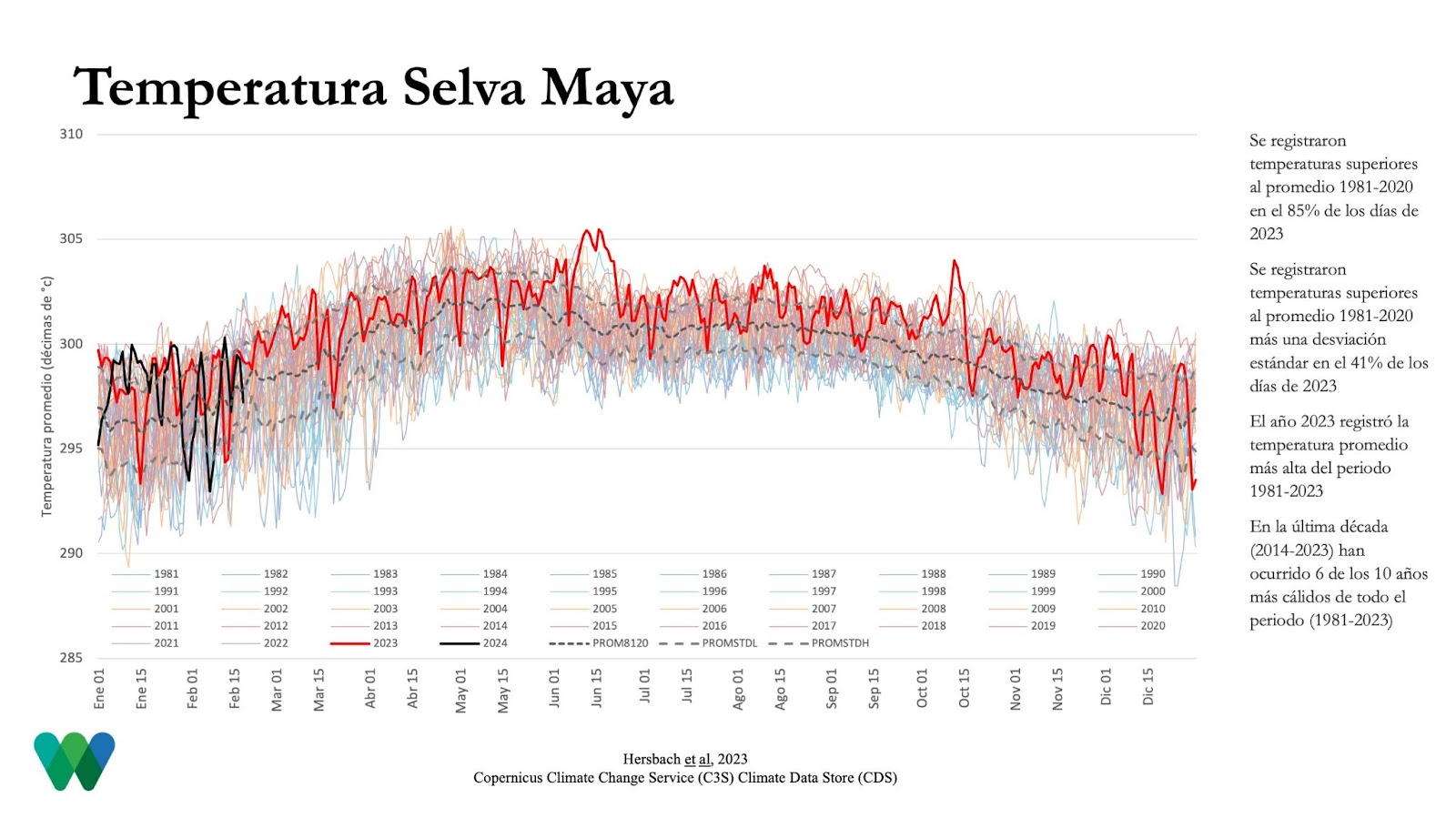

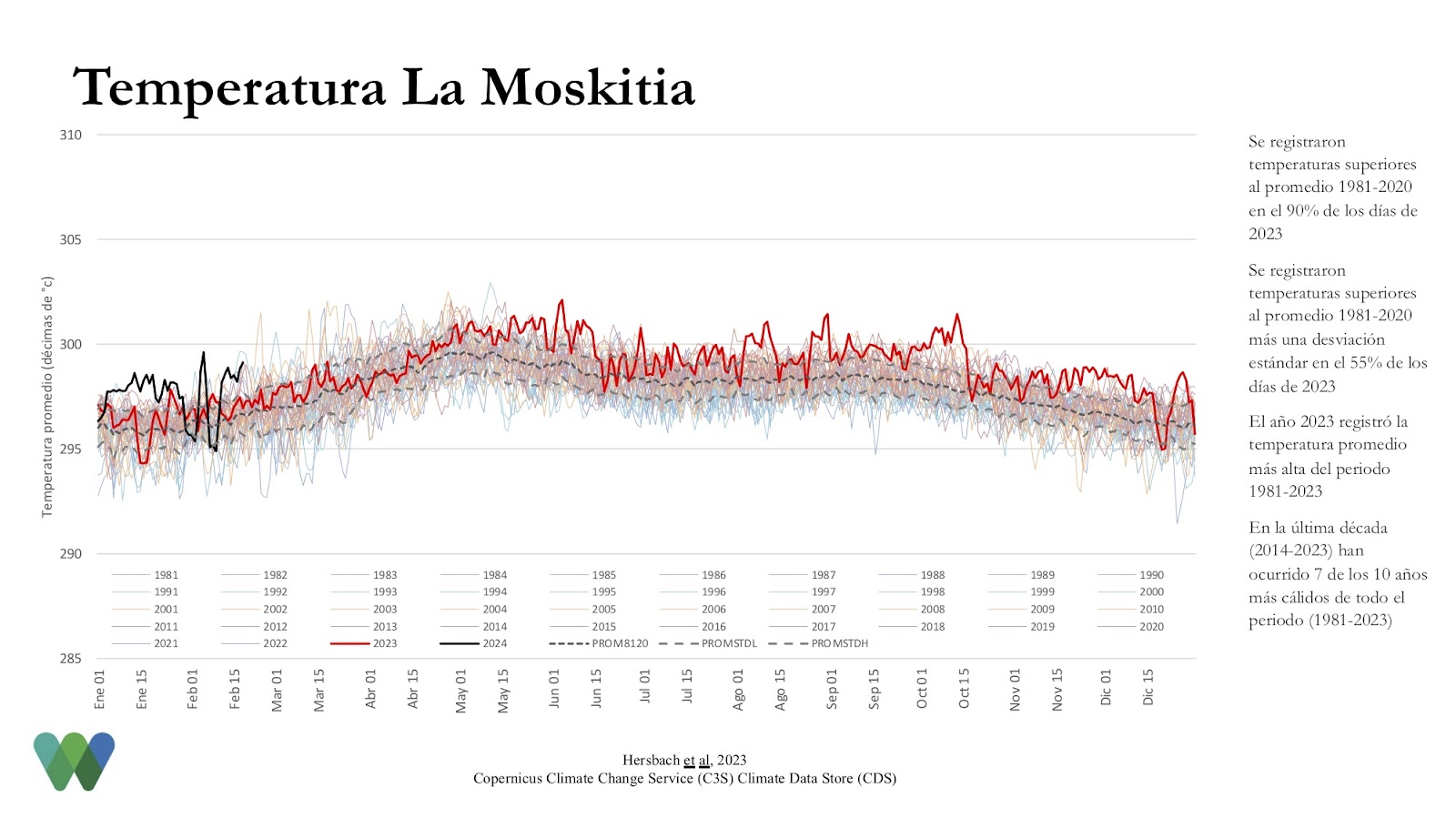

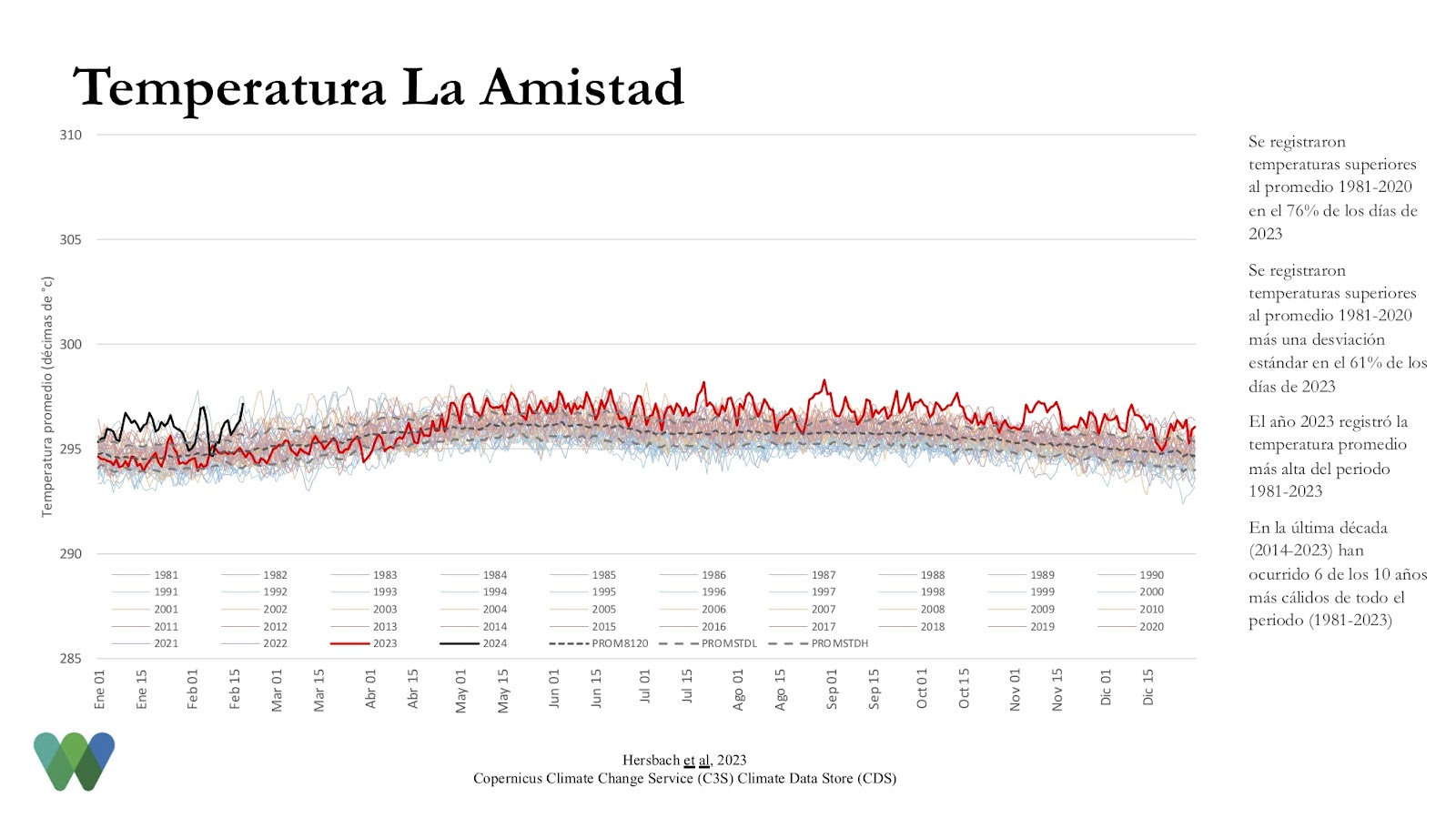

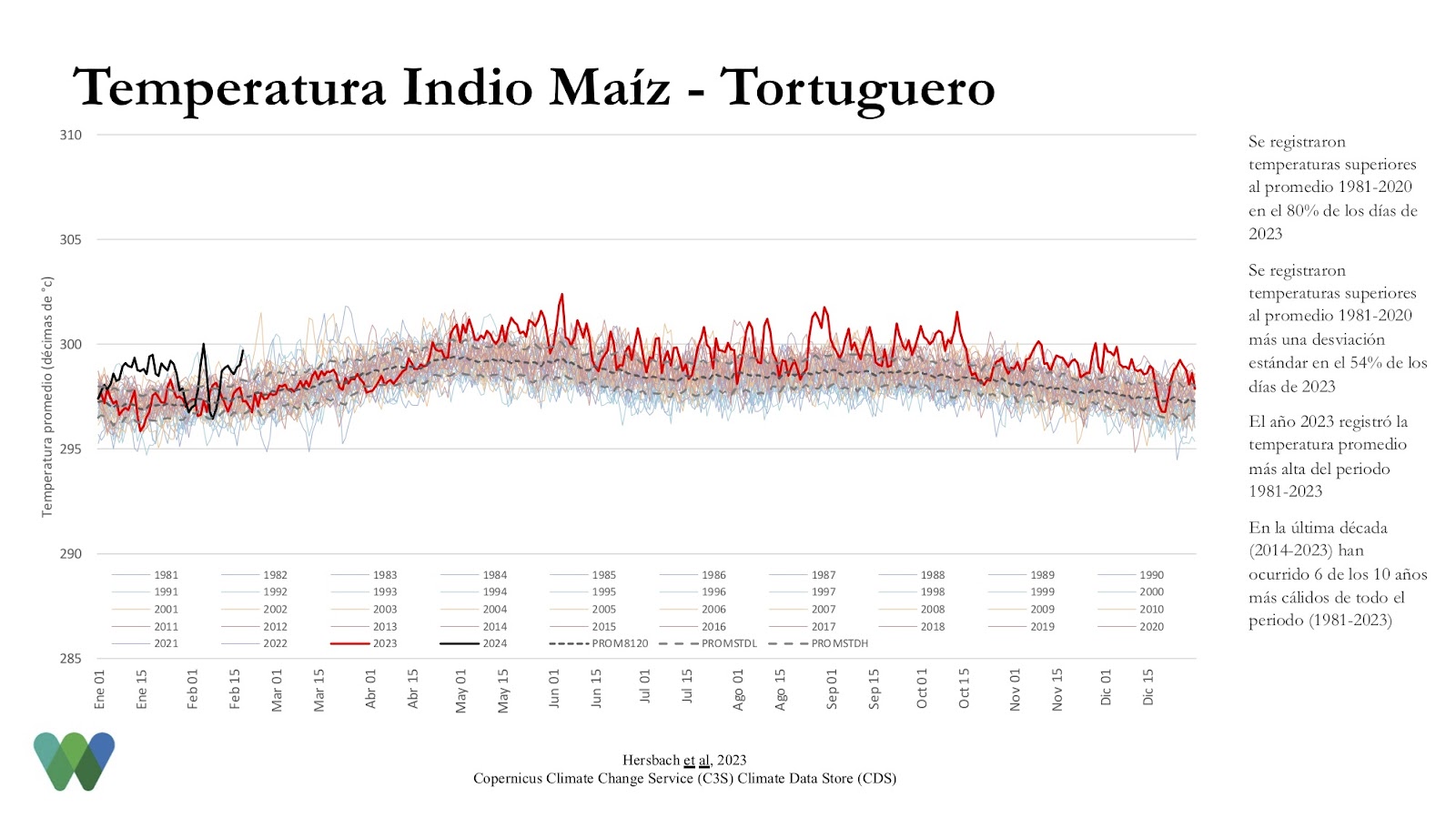

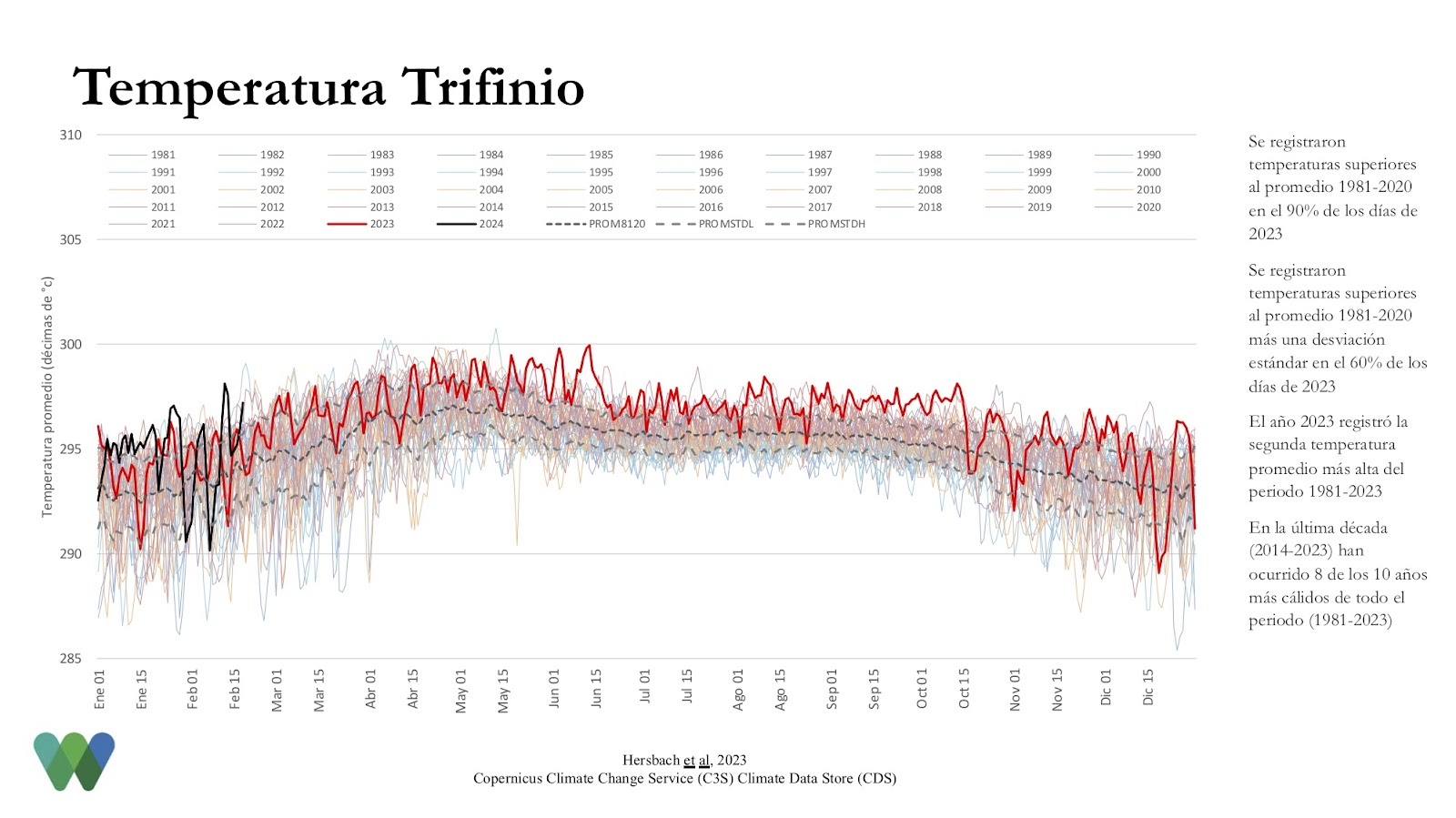

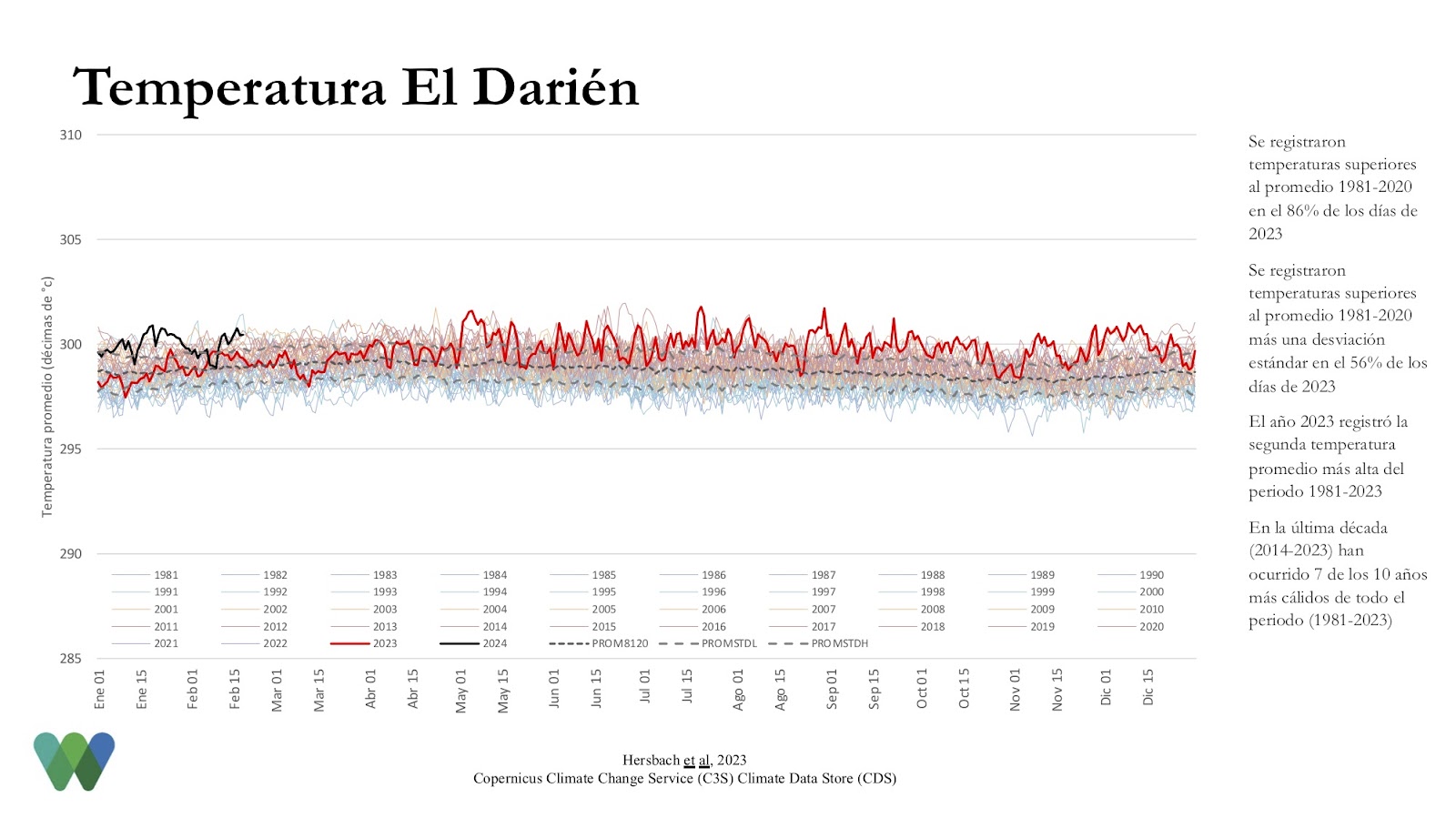

In an analysis conducted by WCS, based on data from Climate Reanalyzer and the ERA5 data set, a sustained increase in temperatures is evident in the 5 Great Forests of Mesoamerica with respect to the reference period 1981-2020.

In 2023, the Maya, Moskitia, Indio Maíz-Tortuguero, La Amistad and Darién forests recorded temperatures above the historical average on more than 75% of the days of the year, with peaks that exceed the average, plus one standard deviation on more than half the days for some forests. In particular, the year 2023 has been the warmest or one of the warmest within this period for all the mentioned regions, marking a clear trend towards an increase in temperatures. The last decade has been particularly warm, with 6 or 7 of the 10 warmest years on record since 1981. This pattern highlights the need to consider climate variability and its potential impacts on the conservation of these critical ecosystems.

(Click to enlarge)

If we consider historical patterns during El Niño years, particularly the effects observed in Mesoamerica during dry and fire seasons, we could anticipate consequences for this year similar to those experienced in previous critical moments. For example, in 1998, El Niño contributed to one of the most severe fire seasons, devastating large areas of the Maya Forest, affecting biodiversity and exposing communities to critical levels of smoke pollution. In 2003, the effects translated into prolonged droughts that significantly impacted agriculture, with a notable reduction in water availability that triggered restrictions and conflicts over water resources. Similarly, in 2016, the combination of extreme heat and low rainfall exacerbated forest fires in the Darién region, highlighting the vulnerability of these areas to extreme weather events. Taking these precedents into account, it is plausible that this year we will face intensified fire events and longer periods of drought, which will require management and preparation focused on mitigating risks to the ecosystems and human communities of Mesoamerica.

III. Regional fire prevention and El Niño preparedness efforts

The climatological phenomenon of El Niño, in addition to environmental impacts, such as anomalies in precipitation and droughts, also generates economic repercussions. Felisa Navas Pérez, president of the Cruce La Colorada Comprehensive Forestry Association (AFICC) of Petén, Guatemala, highlights this aspect by pointing out: “We have a forestry concession where we use various non-timber resources, such as xate and allspice, and that is why we do not want the forest to be destroyed.”

During a field trip to visit plots undergoing restoration efforts in the Multiple Use Zone of the Maya Biosphere Reserve, Estuardo Miguel Díaz, from AFICC, shares that an intense forest fire season is expected. Theyhey are already preparing for this with the maintenance of fire breaks: “We have 42 kilometers of roads around the areas under restoration that we must keep clear. This way, if a fire reaches the area, we will be able to control it effectively.”

Currently, this area has a commission dedicated to preventing and combating forest fires that has gradually been strengthened. With the work of the community brigade, constant monitoring is maintained in the area and with the use of technology, such as drones, they carry out more precise work without the risks that direct combating of forest fires may entail. Antonio Juárez Romero, also of AFICC, comments that they have noticed great changes, because they now have a trained brigade and the work is better coordinated with the National Protected Areas Council (CONAP) and other partner organizations.

Photo: Area undergoing restoration in the Maya Biosphere Reserve. Currently, the areas are protected with firebreaks which are maintained by the local communities that live around them, in collaboration with other organizations. ©César Paz / WCS Guatemala

Photo: Area undergoing restoration in the Maya Biosphere Reserve. Currently, the areas are protected with firebreaks which are maintained by the local communities that live around them, in collaboration with other organizations. ©César Paz / WCS Guatemala

Elsewhere, in Belize, efforts are also underway in preparation for an expected intense fire season in the Maya Forest Corridor. Work is being done to open and maintain firebreaks, and train field personnel and community members in fire management, including raising awareness through a campaign whose motto is: "Ignite awareness, extinguish negligence: Your responsibility, our future."

Focus is also being placed on developing the resilience of local communities, with activities that include climate-smart community plans for the Mahogany Heights community and initiatives such as climate-smart agricultural practices within the Community Baboon Sanctuary.

In Honduras, following the judicial recovery of approximately 300 hectares of forest at the site known as Cayo Cañones, a restoration plan was designed that includes the opening of firebreaks to prevent damage to the natural regeneration of the predominantly pine forest at the site. Simultaneously, in coordination with the Forest Conservation Institute (ICF), prevention work and eventual firefighting will be carried out in the Mabita and RusRus communities with the purpose of reducing the risk to Scarlet Macaws, which nest in the pine savannah of this region of the Honduran Moskitia.

Together, these actions reflect the commitment of communities and organizations in Mesoamerica to face the impacts of El Niño. Science and community collaboration will be fundamental tools to address these challenges.

Photo: Community brigade in charge of breach maintenance, prevention and combating wildfires.

Photo: Community brigade in charge of breach maintenance, prevention and combating wildfires.