Every year, millions of migratory birds make cross-border journeys to spend the boreal winters in Central and South America. From landscapes as distinct as New York City and the rainforest of the Mosquito Coast (between Nicaragua and Honduras), species such as the Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina) face numerous threats throughout the continent. Such threats include climate change, habitat loss and fragmentation, wildfires, use of agrochemicals, air pollution, and wildlife trafficking, among others.

Why is bird conservation important? In the words of Marcial Córdova, coordinator of the WCS Guatemala Bird Program: “Birds play an important role as pollinators, they also help eliminate pests and, above all, keep forests healthy.”

Photo: All participants practiced and improved their techniques for physical handling of birds, including removing birds from nets and placing metal bands.

Photo: All participants practiced and improved their techniques for physical handling of birds, including removing birds from nets and placing metal bands.

Therefore, there are multiple efforts from communities, non-governmental organizations, academia and governments to implement initiatives that reduce threats and direct funding for bird conservation. In this context, the “Joint NABC Bird Banding Certification and Bird Genoscape Project Workshop with an introduction to Motus” convened more than 25 bird specialists from Belize, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Spain and the United States of America. Spanish, English and Creole were heard, but everyone came together for a common cause: understanding the ecology of birds through their complete annual cycle and identifying migratory routes, in order to improve conservation strategies.

Photo: San Pedro River. “Las Guacamayas” Biological Station, “Laguna del Tigre” National Park, Guatemala.

Photo: San Pedro River. “Las Guacamayas” Biological Station, “Laguna del Tigre” National Park, Guatemala.

The workshop, held at the Las Guacamayas Biological Station in the heart of Guatemala’s Maya Forest, consisted of a 9-day training for participants to become certified as bird banders by the North American Banding Council (NABC).

But what exactly is banding? It is a technique by which a metal band with a unique identification number is placed on a bird's leg, after which the bird is analyzed to gather important data: species identity, molt, sex, age, weight, body condition and reproductive status to calculate vital rates, information that is stored in the database of MoSI (Winter Survival Monitoring) programme stations.

MoSI stations are a collaborative monitoring network managed by the Institute for Bird Populations (IBP) that currently includes more than 250 stations in 22 countries. With bird banding and data collection, it is possible to answer questions such as: What are the most severe threats to the survival of the species? Arte threats on the wintering grounds more critical? Which factors underlie population declines? And what can we do to reverse those declines?

Photo: The birds were handled under a strict safety and ethical protocol.

Photo: The birds were handled under a strict safety and ethical protocol.

Throughout the entire banding process, birds are carefully handled to avoid the slightest damage, following a methodology approved by NABC. To capture them, nets are opened during the early hours of the morning and are subsequently checked every 30 minutes. Trapped birds are safely untangled, while a table awaits them in the wilderness of the Maya Forest, equipped with a variety of tools and books. With the bird in hand, various data are recorded for later entry in the MoSI database. The instructors supervise the entire process, in a constant dialogue; the band is placed, numbers are written down and the bird is released.

Steve Albert from the Institute for Bird Populations explains "The MoSI program's systemic network of bird banding stations can be indicative of what is happening in the environment, as birds accumulate toxins over the course of their lives and manifest the effects of climate change very strongly. For example, the first signs of the dangers of lead in the environment were obtained through studies of birds," says the researcher.

On the age of birds, Holly Garrod from BirdsCaribbean clarifies that we can only estimate relative age - whether they are younger or older. It is not possible to calculate exactly whether they are three or five years old, but through recaptures we can obtain more precise information on how long they live.

“One thing that really impressed me, when I started banding, was that we caught a Wilson's Warbler (Cardellina pusilla), which is a migratory bird weighing about 10 grams. And we caught that same bird in California and when we looked up its band number, we found out it was 10 years old. And we've found them wintering in Costa Rica, so we may not know exactly where they've spent the winter, but it means that that bird has gone back and forth between the US and Central America 20 times, essentially going once and it has returned once and it has returned...Holding a 10-year-old bird in your hand, a bird that we might think does not live more than two or three years, is impressive to me.

-Holly Garrod-

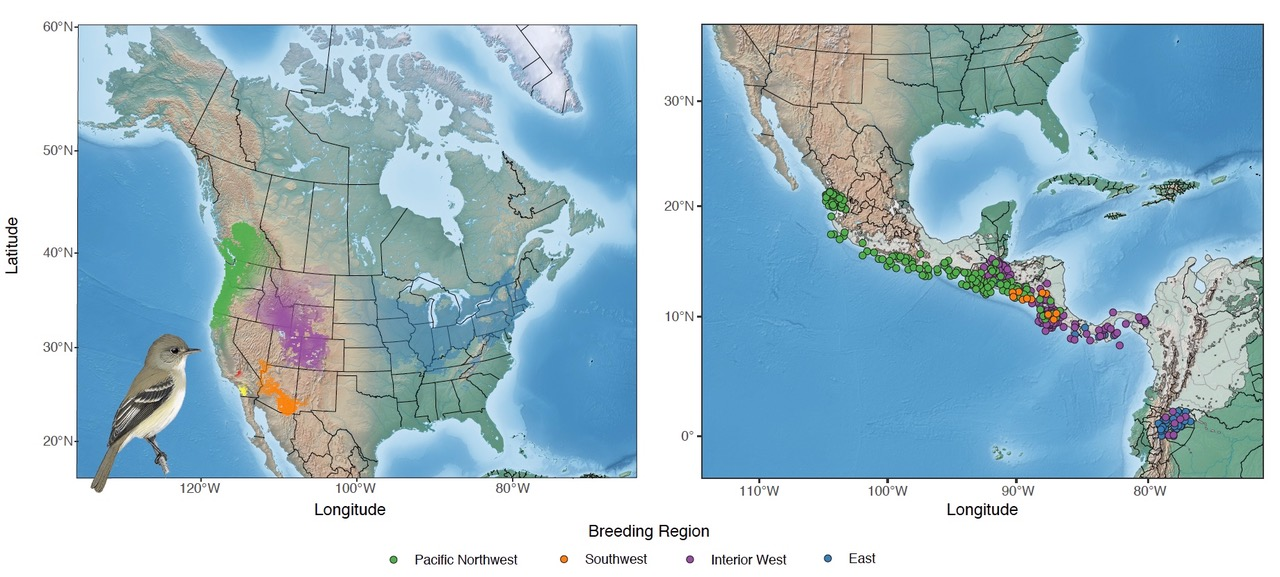

The workshop also featured theoretical sessions, including one by Dr. Kristen Ruegg, director of the Bird Genoscape Project. The Bird Genoscape Project uses genomics to understand the migratory connectivity of bird species, identifying subpopulations that exist across the breeding range of a migratory species and investigating where these subpopulations go during the boreal winter. The project has built a network of researchers who study migratory bird populations throughout their full ranges and annual cycles using DNA from feathers. They currently have a collection of feather samples from 200,000 birds from North, Central and South America, which they are using to create connectivity maps for 100 North American migratory species. The species list can be found here.

Map by Bird Genoscape Project. The creation of a "genoscape” (or genomic landscape) of a species allows us to better understand specific population trends and the threats that cause them.

Map by Bird Genoscape Project. The creation of a "genoscape” (or genomic landscape) of a species allows us to better understand specific population trends and the threats that cause them.

Adam Hannuskela, an ornithologist with the Sonoran Joint Venture, shared a presentation on Motus, an international research network that uses automated radio telemetry to track bird movements. Whereas recapture of a particular banded bird at a MoSI station is unlikely, Motus stations are continuously active and pick up the radio signals of any marked bird passing within a radius of about 15 kilometers, so the growing Motus network allows us to learn much more quickly where individual birds are going and the migration patterns of species. Adam also demonstrated the equipment and the steps involved in installing a transmitter on the back of birds. Motus stations currently exist in Canada, the United States of America and some Latin American countries, such as Guatemala, Belize, Colombia, and the Southern Cone.

In her talk, Sarah Fanelli, Project Manager for the US Department of the Interior (DOI) International Technical Assistance Program (ITAP), explained the areas of impact of the Selva Maya project, which covers three countries; Guatemala, Belize and Mexico and provides technical assistance on biodiversity issues in protected areas.

“DOI and USAID’s work, through its in-country partners and programs helps safeguard the biological integrity of the Maya Forest. This workshop is an example of that.”

-Sarah Fanelli-

Abidas Ash, Amanda Carpenter, Sheela Turbek, Holly Garrod, Juan Carlos Fernández-Ordóñez and Sergio Gómez Villaverde also shared about their projects, methodologies and results in their respective countries.

In total, 2 participants were certified as banders and 8 as banding assistants. The rigorous certification helps banders to generate high-quality information and ensures the least possible impact on the birds assessed. The process is very demanding as it requires days of training and review of complex and constantly evolving techniques.

Photo: The participants at the “Las Guacamayas” Biological Station at the end of the workshop.

Photo: The participants at the “Las Guacamayas” Biological Station at the end of the workshop.

“The opportunity to come here and have trainers available who can tell you what the molting processes are like, what the difference is between one plumage and another, why they come, what they are doing here in terms of changing plumage and reproductive status. For those of us who work with birds, it is a unique opportunity to learn about their populations and routes in Central America.”

-Heydi Herrera-

“Do you have a favorite bird, Steve?” “-No, not really, I don't have any favorites. I love them all, even the condors, even the smallest warblers.”

-Steve Albert-

Participants came from organizations such as; the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), FUNDAECO, the University of Belize Environmental Research Institute (UBERI), Belize Audubon Society (BAS), Foundation for Wildlife Conservation (FWC), Sonoran Joint Venture, Toledo Institute for Development and Environment (TIDE), Colorado State University, and the International Technical Assistance Program (ITAP) of the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI).

This workshop was supported by USAID, the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI), a grant to K. Ruegg from the National Science Foundation (Award #1942313), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service via an NMBCA grant awarded to the WCS Nicaragua program, the North American Banding Council, Balam, and the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS).

For more information about the WCS Mesoamerica Bird Program, contact:

Anna Lello Smith / alellosmith@wcs.org

Media / Claudia Novelo Alpuche / cnovelo@wcs.org

Text by the WCS Mesoamerica and the Caribbean team and other collaborators / Photos by Claudia Novelo Alpuche