“By our very nature, and especially among Indigenous Peoples, we have an inherent drive to protect Mother Earth.” Lourdes Frasser Rojas, a member of the Brunka community and the Ecocultural Association of Indigenous Art and Tourism So Cagrú de Boruca, shares this message from her workshop located in the province of Punta Arenas, which is considered part of the buffer zone of the La Amistad International Park.

Together with a group of skilled craftswomen, they create masks from balsa and cedar wood, skillfully depicting the local biodiversity, featuring jaguars, macaws, and colorful plants. They also craft textiles and offer culinary experiences through Indigenous tourism. Lourdes adds that, in response to the pandemic, they had to reinvent themselves and simultaneously embarked on a reforestation project.

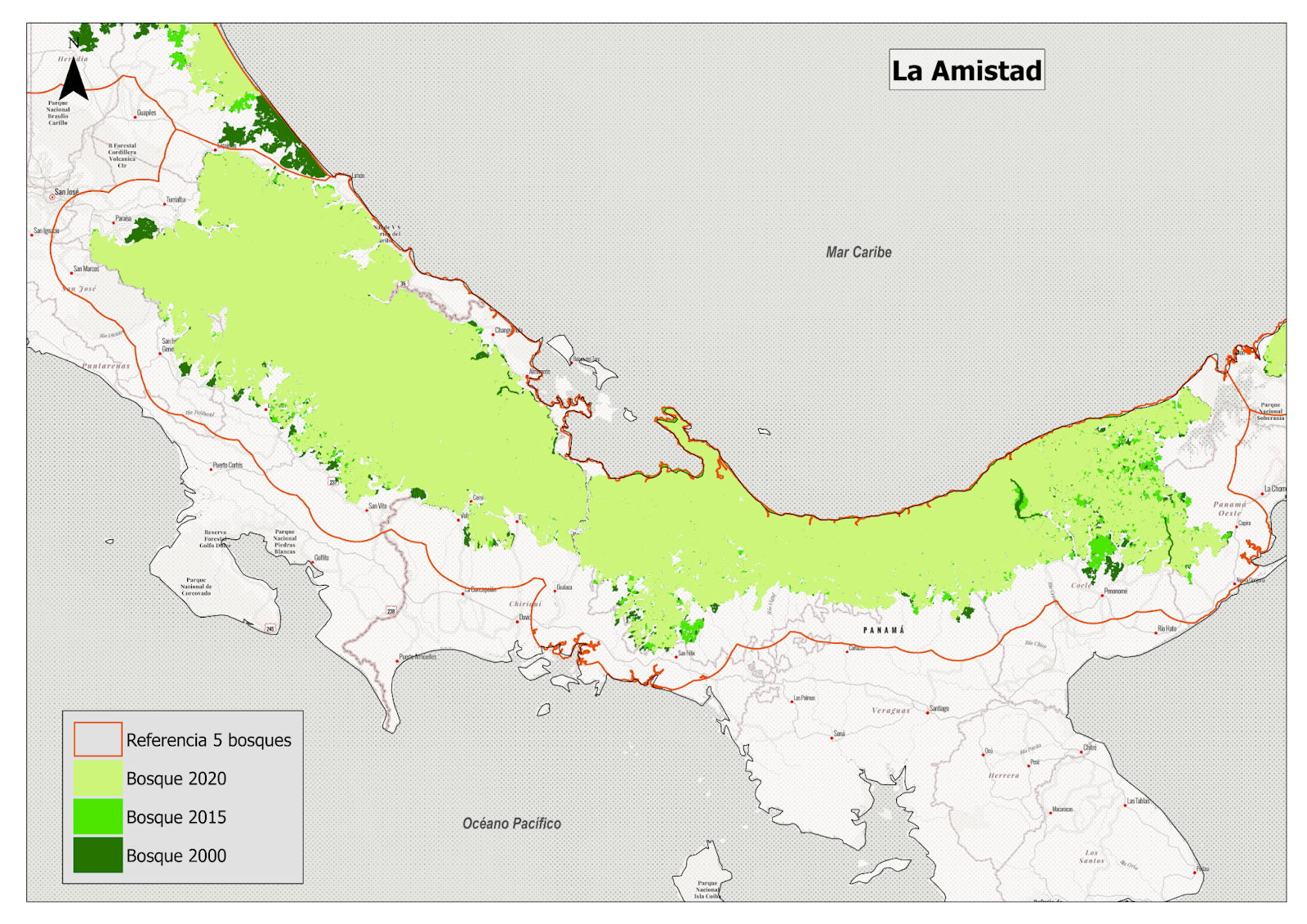

La Amistad is one of the Great Forests of Mesoamerica, situated in the Talamanca Range in Costa Rica and western Panama. It is home to species such as jaguars, tapirs, peccaries, and harpy eagles. La Amistad has been designated a World Heritage site by UNESCO since 1983.

According to a study conducted by the University for International Cooperation (UCI) on threats and land use change in the 5 Great Forests, a total of 185,594 hectares of forest cover has been lost in the past 20 years, with an average annual loss of 9,280 hectares. The peaks of deforestation occurred in 2013 and 2014, during which 14,263 and 14,430 hectares were lost, respectively. The primary cause is largely attributed to an increase in shifting agriculture.

Photo: Lourdes Frasser Rojas holds a mask made by women from the community.

Photo: Lourdes Frasser Rojas holds a mask made by women from the community.

RESTORE OR REFOREST

Conflicts that are prominent in this forest include the expansion of pineapple cultivation, oil palm plantations, and cattle ranching. These activities lead to the use of herbicides and chemicals, the introduction of invasive grass species, soil compaction, and erosion. Rodrigo de Sousa, the manager of the Tropical Forest Program at OSA Conservation, emphasizes, "These are the three land uses that have the most significant impact on the environment, not only due to the type of crops but also because of the technological practices associated with their exploitation."

According to a recent article titled “Improvements in climate and biodiversity outcomes through restoration of forest integrity” published by Trillion Trees and Conservation Biology (CONBIO), restoring degraded areas provides more significant and faster benefits for biodiversity and climate mitigation compared to actions solely focused on reforestation.

What is restoration? Restoration refers to the process of returning degraded forests to their natural state. This involves various activities such as tree planting, removal of invasive species, and enhancement of soil quality. Restoring degraded forests contributes to climate change mitigation by sequestering carbon, while also offering habitat for wildlife and other crucial ecosystem services. Restoration can also yield economic benefits, including timber and non-timber forest products. It serves as a crucial tool for preserving biodiversity and mitigating the impacts of climate change.

Map: Forest loss from 2000 to 2020. Source: WCS 2022.

Map: Forest loss from 2000 to 2020. Source: WCS 2022. Photo: Plot undergoing restoration process by the field team of OSA Conservation in the buffer zone of La Amistad International Park, Costa Rica.

Photo: Plot undergoing restoration process by the field team of OSA Conservation in the buffer zone of La Amistad International Park, Costa Rica.

Tangible evidence of these processes is visible on the farms managed by OSA Conservation, where the vegetation has rebounded, and biodiversity is making a gradual comeback. OSA Conservation is presently engaged in monitoring activities concerning the growth of planted trees, natural regeneration, biodiversity, and soil health. Their efforts primarily involve close collaboration with the local community and farmers in the region, within a larger regional restoration network comprising 250 farms and 10 partner communities. The restoration initiatives encompass the propagation and planting of 40 tree species that are either threatened or endangered.

THE QUETZAL: THE EMBLEM BIRD

Within the buffer zone, in San Gerardo de Dota, at an approximate altitude of 2,600 meters, you'll find "Paraíso Quetzal Lodge," a hotel managed by families dedicated to protecting over 80 hectares of primary forest, which harbors a vast diversity of flora and fauna. The Resplendent Quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno) is a notable highlight, as it can be observed every morning from December to April. This bird previously faced risks due to habitat destruction, as explained by Jorge Serrano Salazar, the site manager and coordinator of the Kabek conservation project; "Economic activities used to revolve around deforestation, but nowadays, our focus is on birdwatching and ecotourism, which provides both economic income and forest conservation."

Photo: William Solano Granados, member of the Kabek project, holds a quetzal feather.

Photo: William Solano Granados, member of the Kabek project, holds a quetzal feather.

William Solano Granados, one of the farmers involved in the Kabek project, reflects on how he used to believe that conservation wouldn't yield any benefits: "I didn't appreciate nature, but now I feel connected to it. Sometimes, I even sense that the birds communicate with me." He points out that trees like the aguacatillo are highly frequented by quetzals, and he is committed to looking after them, recognizing that the benefits extend to these magnificent birds as well.

“I CAN CONTRIBUTE TO CONSERVATION THROUGH MY COFFEE, MY CACAO, MY VEGETABLES”

Another woman who works in the province of Punta Arenas is Yendri Suárez Chacón, president of the La Amistad Producers Association (AsoProLA) and member of the biological monitoring brigade “Fuente de Vida” that, collectively, generates information about the biodiversity present in the La Amistad corridor. She explains, “In the area we have found mostly pumas and ocelots, although we have certainly seen jaguars, as well as deer, tepezcuintles, tapirs and all kinds of amphibians and reptiles”.

Yendry reflects on the crops they cultivate, noting that coffee is a deeply rooted cultural and family tradition, while cacao is a more recent addition. They have embraced cacao as a crop that significantly contributes to biological connectivity. Their way of life and economy are centered around agriculture and the services connected to it, including rural tourism. Therefore, the significance of this productive initiative is highlighted as it sustains the livelihoods of the local community.

"I can contribute to conservation through my coffee, my cacao, and my vegetables, and that is what we promote. Because when you understand something, you are able to identify with it and love it," Yendry concludes.

BIOLOGICAL MONITORING IN UJARRÁS

The Indigenous biological monitoring brigade “Ujarrás” holds years of experience as park rangers and is located in the Talamanca Mountain Range. In a visit carried out by WCS and Costa Rica Wildlife Foundation, the patrol team presented some of the activities they implement to defend their territory, especially against threats such as hunting, logging and forest fires.

Photo: Tapir (Tapirus bairdii) captured in La Amistad International Park, Costa Rica.

Photo: Tapir (Tapirus bairdii) captured in La Amistad International Park, Costa Rica.

Carolina Fernández Zúñiga, specialist in environmental education and member of the patrol team, shares that they also help with the installation of camera traps in strategic points for surveillance and monitoring of certain animals, such as the tapir.

For Roy Rojas Salazar, also a member of the patrol team, one of the main challenges is the complexity of moving around the more than 19,000 hectares of territory they monitor; however, they have managed to organize themselves to cover 12 different sites. They hope that soon, with SMART training, they will be able to implement the use of this tool, just as the San Jerónimo group does, in the buffer zone of the Chirripó National Park.

Photo: “Ujarrás” biological monitoring brigade and the Re:wild team, Costa Rica Wildlife Foundation and WCS Mesoamérica.

Photo: “Ujarrás” biological monitoring brigade and the Re:wild team, Costa Rica Wildlife Foundation and WCS Mesoamérica.

SMART: A KEY TOOL FOR PARK RANGERS, COMMUNITIES AND GOVERNMENTS

In the community of San Jerónimo, in the province of Pérez Zeledón, there is a well-established group known as the "Guardians of Biodiversity." This group conducts regular patrols to combat environmental threats such as poaching, illegal logging, and illicit marijuana plantations. Merlin Gamboa Arias, a member of the brigade and a guide, explains that the group was formed out of the necessity to have individuals who are dedicated to environmental protection, which is crucial for the community since ecotourism plays a significant role in their economy.

For this community, the use of the SMART tool has enabled them to create threat maps of their area, providing valuable data to the authorities. With support from organizations like WCS, Re:wild, and Costa Rica Wildlife Foundation, this trained group extends its coverage not only to their own community but also to neighboring communities like El Zapotal and San Rafael.

The SMART tool is specialized software designed to assist in the management and conservation of wildlife and landscapes. It supports a wide range of activities, including conservation, law enforcement, tourism management, and sustainable use of natural resources. For Lidia Quiroz Solís, one of the female patrol members in the area, the knowledge that more organizations are joining the effort to protect La Amistad International Park brings her joy and strengthens her resolve to continue their work.

Photo: Guardians of Biodiversity, San Jerónimo, Costa Rica.

Photo: Guardians of Biodiversity, San Jerónimo, Costa Rica.

Photos and texts by Claudia Novelo Alpuche. Camera trap photographs by WCS and allies. Maps by Marco Martínez. The opinions expressed in this information product are the responsibility of its author(s), and the GCF cannot be held responsible for any use made of the information contained therein.