"Once, this place was a thriving forest, with xate, guano, macaws, and an abundance of life. But regrettably, there were individuals who didn't consider the consequences of their actions and began to despoil it, transforming it into cattle pastures," laments Sabino Véliz Morales, as he endeavors to uproot invasive fern from an illegal pasture. "If we can't get rid of this stubborn grass – and it's not just a little, it's a lot – reforestation efforts will face significant challenges," he observes. Nevertheless, Sabino remains hopeful and envisions a future where, in a few years' time, he might even harvest allspice.

Left photo:Illegal cattle ranching installed in the buffer Zone of the Maya Biosphere Reserve. Right photo: César Paz of the WCS Guatemala Program holds an invasive fern, known as "chispa" (Pteridium aquilinum), a species that normally grows in degraded soils.

Situated within the Multiple Use Zone of the Maya Biosphere Reserve (MBR), this site under restoration bears the name of "La Colorada" Management Unit. For Sabino, who leads a dedicated team of over 10 individuals camping at this location, a typical workday entails preparing the soil for the cultivation of ramón seedlings (Brosimum alicastrum), mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla), and cericote (Cordia duodecandra) for reforestation purposes. Simultaneously, they tackle the relentless spread of grass that hinders the growth of other species. Currently, these management efforts span six additional sites, covering a total of 428 hectares, through a collaborative partnership between WCS, the National Council of Protected Natural Areas (CONAP), Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Food (MAGA), Association of Forest Communities of Petén (ACOFOP), Nature for Life Foundation, Rainforest Alliance, and more.

Photo: Sabino Véliz Morales, manager of the “La Colorada” nursery, an area in the process of restoration in the Maya Biosphere Reserve of Guatemala.

Photo: Sabino Véliz Morales, manager of the “La Colorada” nursery, an area in the process of restoration in the Maya Biosphere Reserve of Guatemala.

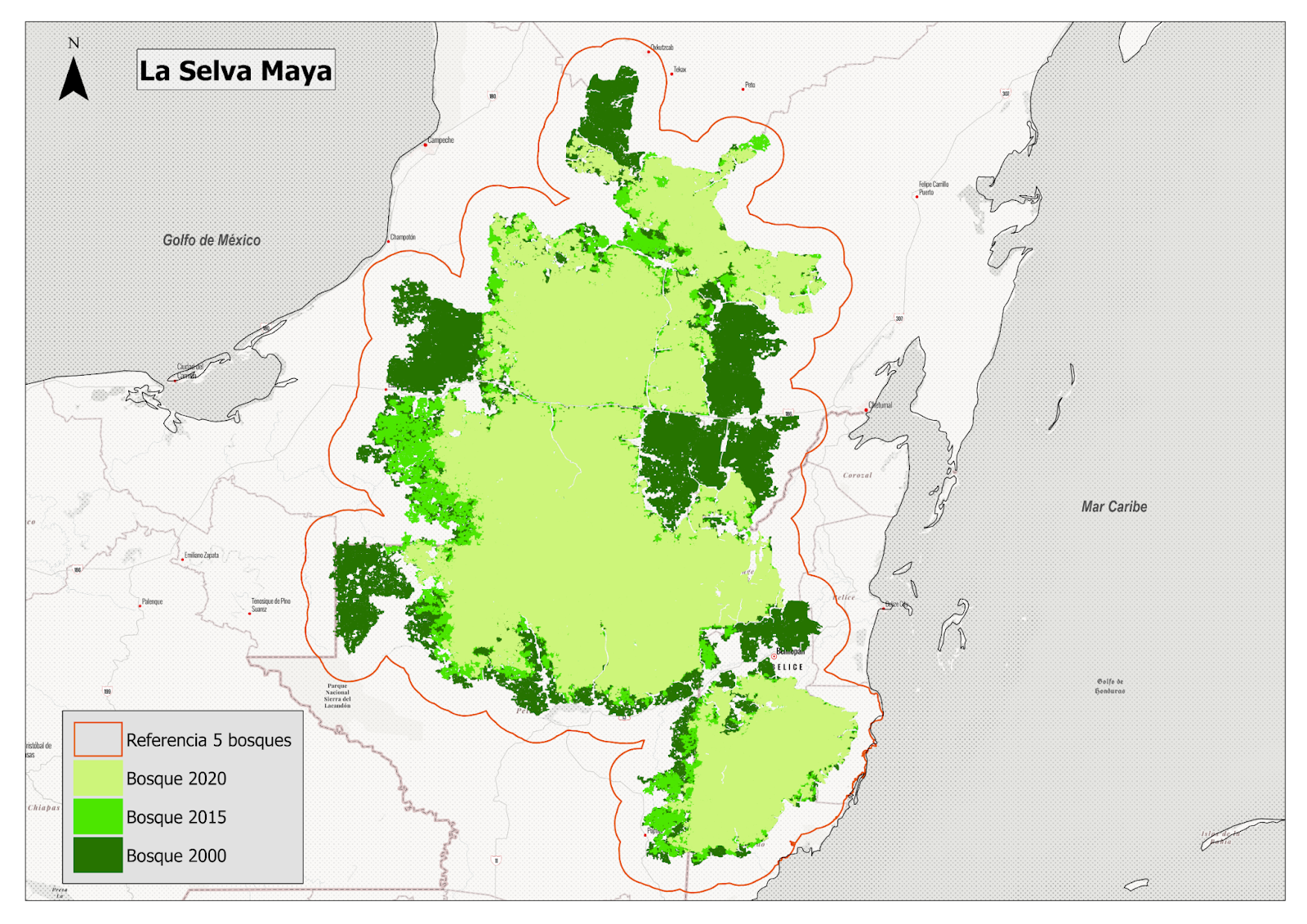

According to the ¨Human Footprint Analysis”, developed by WCS, the Selva Maya lost 33% of its forest cover, equivalent to 18 thousand hectares, between 2000 and 2020. The primary threat responsible for this degradation is extensive cattle ranching, although other threats, such as illegal land encroachment, poaching, wildlife trafficking, forest fires, and oil extraction, persist. However, it is crucial to note that illegal cattle ranching stands out as the most pernicious and destructive form of land use.

An investigation into the smuggling of cattle ranching from Central America to Mexico, carried out by InSight Crime can be consulted here.

The Maya Biosphere Reserve, sprawling across 2 million hectares in Guatemala, shares its boundaries with Campeche to the north, Tabasco to the northeast, and Chiapas to the west, running alongside the Usumacinta River. To the east, it adjoins Belize, and its entire southern periphery is encompassed within the territory of Petén. Presently, the reserve is demarcated into three principal zones:

1. Core Zones (ZN): Comprising five National Parks and four Protected Biotopes, these areas collectively occupy 39% of the reserve.

2. Multiple Use Zone (ZUM): Encompassing 38% of the Maya Biosphere Reserve.

3. Buffer Zone (ZAM): This zone forms a 15-kilometer wide swath along the southern border of the Reserve.

Map: Forest loss from 2000 to 2020 in the Selva Maya of Mexico, Guatemala and Belize. Source: WCS 2022.

Map: Forest loss from 2000 to 2020 in the Selva Maya of Mexico, Guatemala and Belize. Source: WCS 2022.

Since the decree that established the Reserve in 1990, multiple collective conservation and management efforts have been developed, such as the case of the Selva Maya del Norte, which is an organization dedicated to processes of restoration and reforestation. "We focus on the forest; we have the capacity, and that's why we're fighting for these areas, because there is life here, whether it's jaguars, deer, tapirs, various species of birds... corozo, cedar, mahogany, and all of that is a great wealth," shares Eduardo Francisco Acosta Chatá, President of the organization.

Left photo: Francisco Acosta Chatá, president of Selva Maya del Norte. Right photo: Archaeological site of Tikal.

Left photo: Francisco Acosta Chatá, president of Selva Maya del Norte. Right photo: Archaeological site of Tikal. Photo:Jaguar (Panthera onca) capproved in the RBM of Guatemala by WCS Guatemala

Photo:Jaguar (Panthera onca) capproved in the RBM of Guatemala by WCS Guatemala

THE IMPORTANCE OF INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES IN THE MANAGEMENT, USE AND PROTECTION OF FORESTS

In 2013, the population within the Maya Biosphere Reserve (RBM) numbered 175,000 inhabitants. Among them, approximately 160,000 residents were distributed across an estimated 192 communities, predominantly comprising members of the Maya Itza', Maya Q'echi', and around 40 families belonging to the Maya Mopan group.

The preservation of the forest is intrinsically linked to the sustainable resource management practices of Indigenous communities who have nurtured and shaped these lands for millennia. As Carlos Camacho Nassar, a geographer and specialist in environmental conflicts and Indigenous rights, highlights in his recent report titled "Indigenous Territories and Communities in the 5 Great Forests of Mesoamerica,". These territories serve as testament to the fact that the forest is not a natural, virgin, or untouched entity. Instead, it stands as a product of human social production, shedding light on the extent of Maya ancestral lands.

Within the Selva Maya, which is shared by Guatemala, Belize, and Mexico, the presence and distribution of tree species such as ramón and sapodilla provide tangible evidence of the cultural transformation of the environment. They serve as markers of Indigenous management practices that have endured since the initial human occupation of the continent.

Across Mesoamerica, Indigenous lands and territories have been acknowledged through various legal mechanisms. In Guatemala, the forest concession model, established in 1994 and granted for a period of 25 years, presents an opportunity for organized communities residing within the MBR to exercise their rights and fulfill their responsibilities concerning the use and stewardship of natural resources. This model delivers direct environmental, economic, and social benefits to these communities.

Marcedonio Cortave, general director of the Association of Forest Communities of Petén (ACOFOP) recognizes that initially, the lack of credibility and technical, administrative, and economic capabilities represented an obstacle for the communities to obtain these concessions. "Nonetheless, scientific studies now unequivocally demonstrate that forest management can provide sustainable benefits to a significantly larger population," Marcedonio asserts in an interview.

Data from the report Systematization of Community Forest Management of Petén, coordinated by ACOFOP, confirms that in the 9 active community concessions, the annual deforestation rate has been low, and in non-concession areas it has been higher. Currently, the total area granted is more than 485 thousand hectares, where surveillance patrols, maintenance of fire break gaps and monitoring of threat detection points, among others, are also carried out.

ACOFOP, founded in 1997, is an association that represents the community interests of 19 organizations distributed acrossPetén. One of them is Uaxactún, a community located 23 km north of Tikal, which represents an example of successful forest management.

Non-timber forestry, such as the extraction of chicle (Manilkara zapota), ramón, allspice and xate seeds, allow communities like Uaxactún to manage and protect the forest and at the same time strengthen the local economy. Since 2007, Uaxactún has been certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) in its management of the xate palm, an activity that gives life to the community. "Where a xate harvester was today, they will return in 3 to 4 months to gather more xate, and this way the plant continues to thrive, as do we," emphasizes Juan Cruz, a member of the community enterprise.

"In order to export xate, we required FSC certification, but it wasn't until 2005 that we initiated direct exports, primarily to the United States," explains Erwin Maas, a guide and the president of the Community Development Council (COCODE) in Uaxactún, as well as a member of the Management and Conservation Organization (OMYC). Erwin underscores that while the economic impact of this activity is significant, the harvest area covered remains limited due to the methodologies they implement to ensure responsible use. "We prioritize quality over quantity," he asserts.

Left photo: Howler monkey. Right photo: Erwin Maas at the archaeological site of Uaxactún.

Left photo: Howler monkey. Right photo: Erwin Maas at the archaeological site of Uaxactún.

Antonia Álvarez Peralta is in charge of selecting the xate leaves and verifying that they meet the quality standards, ensuring “That they are not stained, burned, or pitted… this work is good for the community and also for women because we obtain benefits,” Antonia highlights. Envisioning and making use of the forest beyond timber only opens up opportunities for greater participation by women in forestry, which is often considered a job exclusive to men.

For Jaime Eduardo España Núñez, a fellow partner in the community enterprise, xate is their "daily bread." He understands that choosing a quality xate leaf is crucial for forest management. Jaime is also skilled in climbing chicozapote trees and is well-versed in the technique for extracting chicle, a skill he learned in his youth. "You see, we make all the cuts, but we don't cut a single branch, and that's why the tree doesn't die," he explains.

Upper left photo: Jaime Eduardo España Núñez extracting xate in the forest. Upper right photo: Erwin Maas explains the process of extracting chicle from. the sapodilla tree.

Upper left photo: Jaime Eduardo España Núñez extracting xate in the forest. Upper right photo: Erwin Maas explains the process of extracting chicle from. the sapodilla tree. Photo: Antonia Álvarez Peralta is in charge of selecting the xate leaves and verifying that the leaf meets quality standards.

Photo: Antonia Álvarez Peralta is in charge of selecting the xate leaves and verifying that the leaf meets quality standards.

Another activity carried out in Uaxactún is community-based tourism, as well as the crafting of colorful dolls created from natural materials. The dolls' bodies and clothing are crafted from corn leaves, while finishing touches are added using moss, mushrooms, and seeds, giving life to these unique creations, a hallmark of Uaxactún artisans. "We must preserve the forests because everything we use in our doll-making originates from there," emphasizes Vislan Gualip Suceli Choc, a representative of Uaxactún's artisans and a member of OMYC.

Photo:Uaxactún doll made with natural materials from the forest.

Photo:Uaxactún doll made with natural materials from the forest.

Concurrently with the forestry concessions, Conservation Agreements have been established in Uaxactún, San Miguel La Palotada, Paso Caballos, and Carmelita since 2009. These agreements represent a community-driven initiative aimed at coordinating agricultural practices, mitigating or curtailing cattle ranching activities, and overall, enhancing management and conservation efforts. This collaborative endeavor involves key partners such as WCS Guatemala, CONAP, Conservation International (CI), the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), and the Darwin Initiative.

FOREST SURVEILLANCE PATROLS IN THE MAYA BIOSPHERE RESERVE

When entering the Multiple Use Zone (ZUM) of the MBR, the first control post is the “San Miguel la Palotada” Command Center, which is operated by CONAP, forestry organizations, specialized police, and military personnel. To enter the ZUM, a vehicle inspection is carried out and official identification and the reason for the visit must be presented.

Since 2009, various areas within a territory that formerly lacked governance are now being guarded. Following the eviction and dismantling of illegal pastures in La Colorada, and after the tragic assassination of community leader David Salguero, responsible for overseeing control and surveillance at the Integral Forest Association Cruce a la Colorada (AFICC) in 2010, the Guatemalan government established 6 Command Posts strategically positioned within the Maya Biosphere Reserve.

At the Inter Institutional Operations Center (COI) of La Colorada, groups of approximately 15 park rangers camp and take turns every 20 days to carry out patrols where they verify and, where appropriate, report illegal activities such as land invasion, poaching, logging, cattle ranching and forest fires. In addition, they install camera traps to monitor the biodiversity of the area. With the use of SMART, a monitoring tool to facilitate the generation and exchange of surveillance and control information in protected areas, the group records the patrols’ coordinates and any anomalous intervention they detect. Another group of military personnel accompanies them on patrols. In other words, they are not alone; they operate as a team with the shared objective of forest surveillance.

Photo: Since 2009, various areas that formerly lacked governance in the MBR are now being guarded.

Photo: Since 2009, various areas that formerly lacked governance in the MBR are now being guarded.

An InSight Crime report on illegal logging in the Selva Maya can be consulted here.

Francisca Ramos Cruz, a ranger and camp cook at the "La Pasadita" Management Unit, reveals that she finds happiness in living there and deeply appreciates the moments of silence and the nocturnal sounds of the forest. She shares her living space with around 20 military personnel tasked with guarding the area. "As a child, I used to dream of living in the mountains... and now, I am fortunate to call them home. It's a delight to witness the forest’s rejuvenation," she remarks.