By Kyaw Thinn Latt

“It used to be quite easy to catch enough fish to feed my family and for me to sell the surplus in the market,” laments Mr. Than Zaw Htay, a coastal fisher in the Kyeintali area of Myanmar, “but these days it is harder and harder to catch enough.”

This situation reflects a growing global trend - where overfishing, rising seas, warming waters, pollution, and poor ocean management, combined with increasing demand for fish, are quickly diminishing fish stocks.

Such trends are particularly worrisome for developing countries like Myanmar, the world’s ninth largest fishing nation. Nearly half of the country’s 53 million people live in coastal regions where local people directly depend on fisheries for their livelihoods and food security. Indeed, scientific surveys conducted here reveal that fish stocks have plummeted by about 80 to 90 percent over the last few decades.

However, as the country’s democratic transition continues to unfold, there are encouraging signs of change that point to opportunities to reverse this trend. Our team at the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) is on the ground in Myanmar working with local people to solve this issue through sustainable, community-led management of marine resources.

Working closely with local partners, and with support from the UK’s Darwin Initiative, WCS has been assisting ten coastal fishing communities to pilot a co-management model for their coastal fisheries. Our initial efforts focused on understanding the communities’ socioeconomic situation and analyzing their current and historic fishing practices.

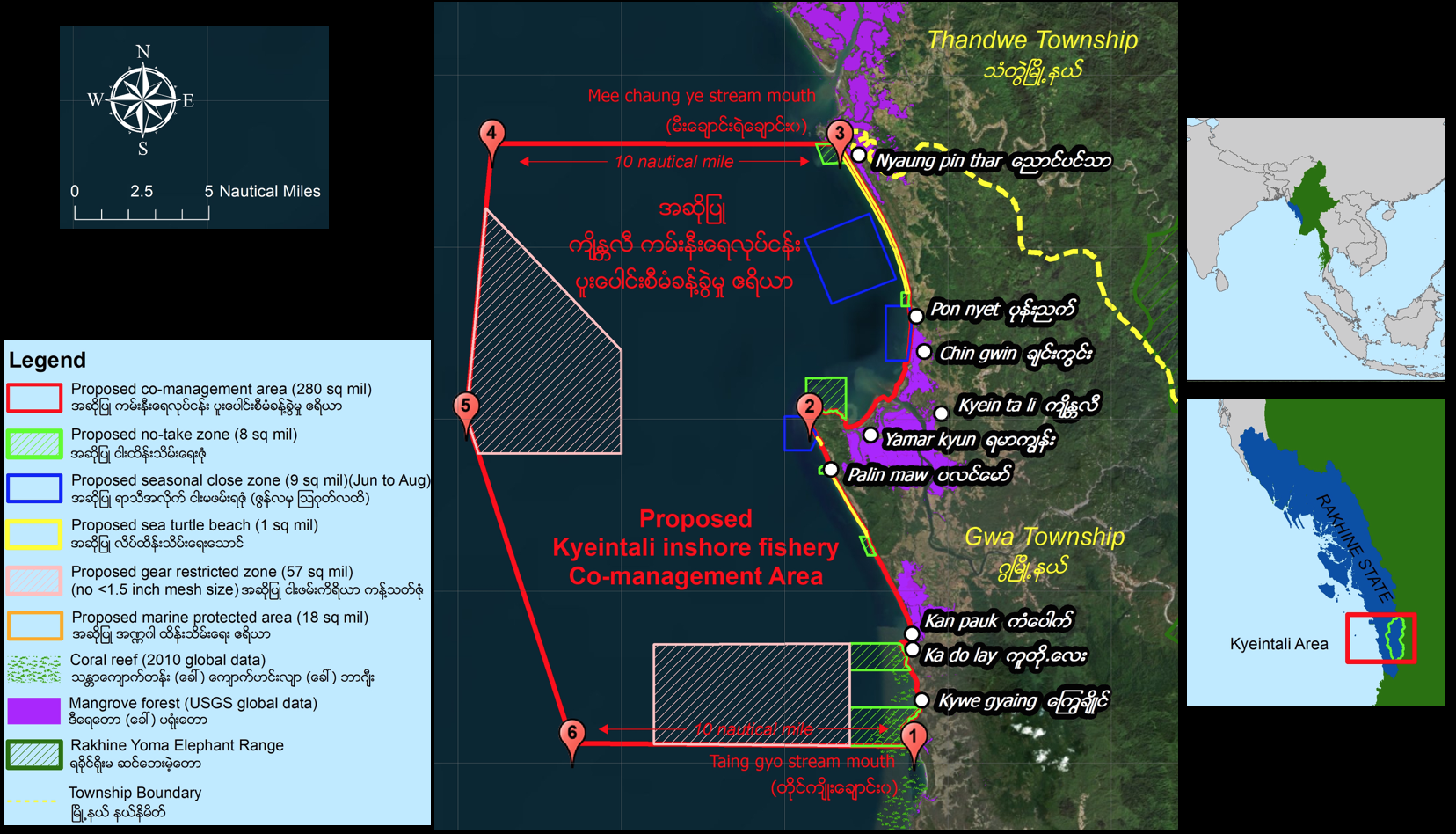

Together, we have mapped fishing grounds and compiled information on preferred gear types, targeted fish species, and seasonal fishing activities. This has aided us in identifying a co-management area and establishing a committee comprising representatives from each of the participating villages to collaboratively oversee the area. Within the 280-square mile co-management area, specific zones – such as no take zones, seasonally-closed areas, and gear-restricted areas – have been delineated by the communities themselves and a co-management plan developed to guide implementation.

Following a successful process of consultations with government agencies, on August 8 Myanmar’s Department of Fisheries formally designated the Kyeintali co-management area, one of the first such arrangements in the country.

“We are very happy about this announcement” exclaimed Mr. Soe Lwin, Chairperson of the Kyeintali Inshore Fisheries Co-management Association, or KIFCA. “This improves our community rights over our traditional fishing grounds. And now, working together with the Department of Fisheries, it will be easier for us to manage this area more sustainably and to stop illegal fishing activities.”

WCS is working side by side with communities such as these to strengthen their access to and rights over their local marine resources, aiding them in enforcing community regulations and prohibiting incursions from commercial fishing vessels.

This co-management model offers a new type of collaboration between local communities and government agencies like the Department of Fisheries, and is a substantial change from the top-down, command-and-control norm of the previous decades of Myanmar’s militarized government.

As part of a broader set of ongoing reforms, Myanmar is in the process of decentralizing natural resource management to state and regional levels, where new local fisheries laws in the country’s coastal states and regions are welcoming community involvement and community-based management in the fisheries sector.

New resource management models such as this – and others like community forestry - help to strengthen cooperation between communities and government officials, aiding local people in gaining greater control over their local resources—and thereby allowing them to derive greater benefits from them.

While this new co-management designation is an important milestone, it is in fact just the beginning. “Now that the co-management area has been declared, we can focus our future efforts on improving fisheries management practices, monitoring fish catches, and keeping offshore boats from fishing illegally in inshore waters,” noted Mr. Thaung Htut, WCS’s Fisheries Monitoring Officer working on the project.

As this early co-management model continues to advance, our goal is to help replicate the approach in new areas and with more local partners and communities. We are assessing new sites where we can help to expand this model across the country and address governance, ecological, and economic needs. The momentum is just beginning, but co-management has the potential to help thousands of fishers and local people along the country’s 2,800-kilometer coastline thrive. Over the long term, fish stocks can recover and local fishers like Mr. Than Zaw Htay will be able to continue putting fish on the family table, thus ensuring a blue future for Myanmar’s coastal communities.

Kyaw Thinn Latt

Senior Strategy Marine Manager

WCS Myanmar