Forensic science has fascinated many of us over the years. From television crime shows to movies, which portray our favourite actor in compelling storylines, investigating and weaving clues together to catch a criminal. Solving crime in real life can however be a strenuous process, with real victims involved. Applying scientific methods and knowledge to criminal investigations is what forensic science does, by incorporating different aspects of science. Forensic science has several sub divisions, one of which is Wildlife Forensics.

‘Wildlife forensics is concerned with providing scientific evidence to inform investigations into crimes against wildlife, focusing on determining the identity of poached or illegally traded wildlife products, and addressing questions relating to the species, geographic origin, relatedness, individual identity and age of samples’ defines TRAFFIC, a leading non-governmental organisation working on wildlife trade.

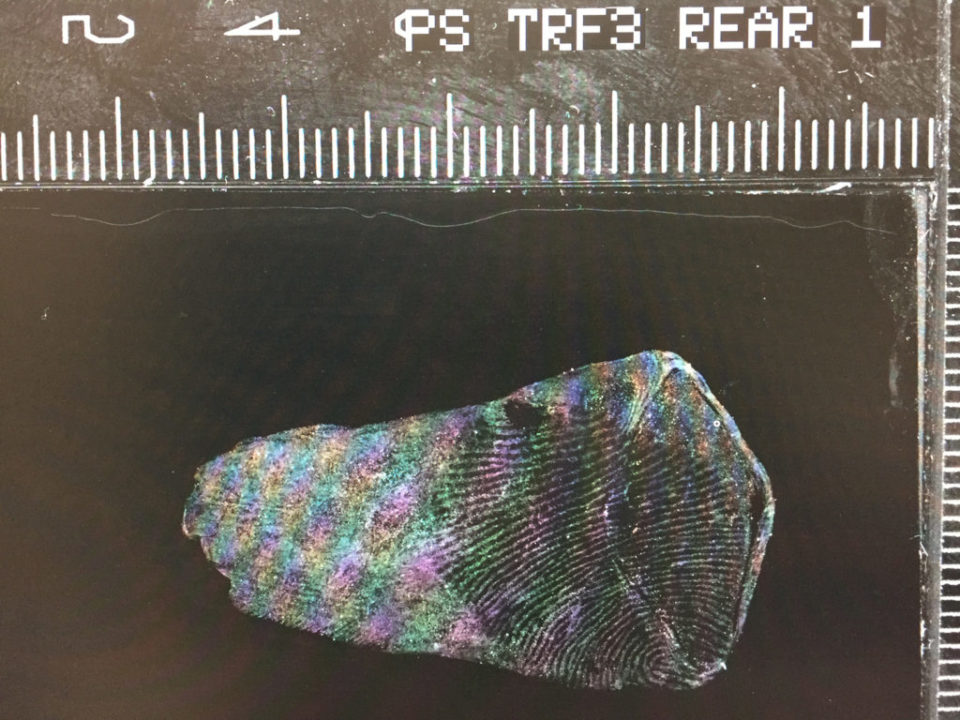

Researchers at the University of Portsmouth and Zoological Society of London (ZSL) have been among those in the forefront of using technology to unravel wildlife crimes. One such method to collect evidences from wildlife crime scenes is gelatine-lifting, keeping the pangolin in mind. This easily helps recover fingerprints from surfaces (scales) using low tack gelatine adhesive, which is able to lift off most dry surfaces. The gel has the potential to also lift other trace materials left on surfaces at a crime scene or on any contraband artefact in the area. The trace materials captured by the gelatine lifters include DNA, pollens, fibres and any other potential evidence lying on the surface.

A scanned pangolin scale with a finger-mark visible.

A scanned pangolin scale with a finger-mark visible.

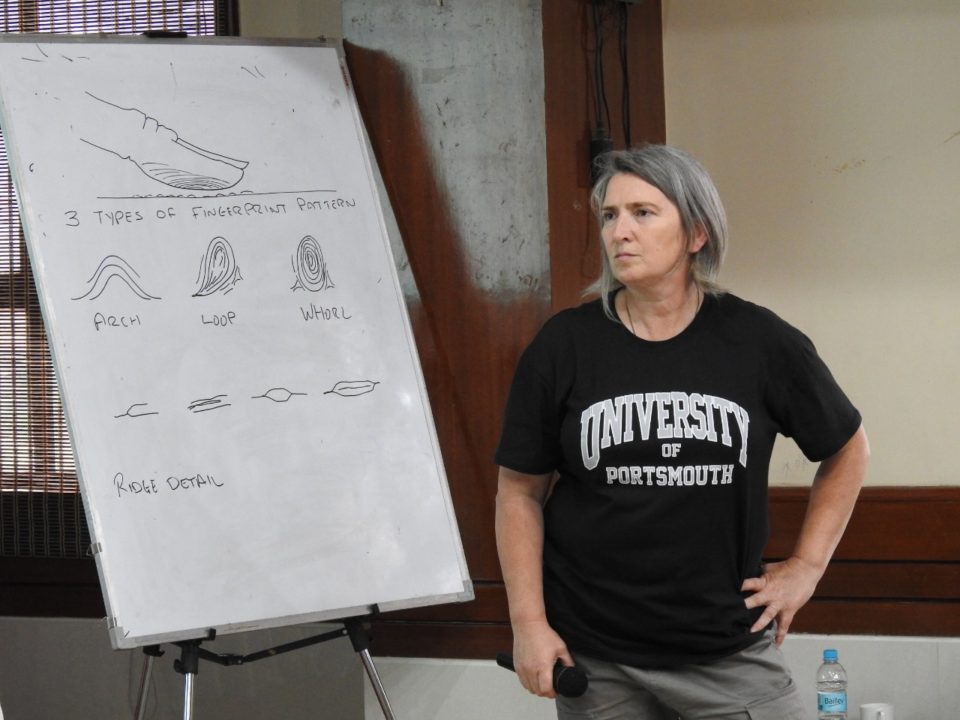

Visiting India this summer were Dr. Nicholas Pamment, Principal Lecturer and Associate Head (Students) at the Institute of Criminal Justice Studies (ICJS); Jac Reed, the Senior Specialist Forensic Technician at ICJS, and Dr Paul Smith, Principal Lecturer, Director of the Forensic Innovation Centre and Innovation Lead at ICJS. The team interacted with students from NCBS, Bangalore and conducted training workshops in Hyderabad and Guwahati talking on the role forensics plays in wildlife crime. During the event at Guwahati and a subsequent visit to Manas National Park, the professors shared some insight into the application of forensics in wildlife crime. Excerpts from the interview with Anisha Iyer:

Role of Forensics in Countering Wildlife Trafficking

Paul: Any type of forensic application is based on the case you are dealing with and the environment within which you are deploying those methods. For example, methods you would deploy at a burglary in the middle of Leicester, is very different from the methods you employ for tiger poisoning in the middle of a forest in India, obviously. The most important thing for me is to establish the link between the animal, the scene and the suspects. And it is also not necessarily about identifying a person. Yes, it is part of it, but it’s also intelligence. Forensics is very often used as an intelligence tool, so it might give you a name, a link to a mobile phone, to a network, to cyber information about the suspect which could then lead to his associates, then could build up to something further up the tree. You can use investigative methods holistically in order to break or disrupt the wildlife crime trade routes or whatever is going on. I think it is incredibly well developed in terms of DNA for identification of the animal. It is also about taking the expertise of people at the scene of wildlife crime, their fantastic knowledge of what’s going on and giving them an extra skill about an investigation mindset, that they can interpret what’s in front in them and gather the best evidence; both for identifying the animal and potentially an individual/ series of individuals or a particular course of action that was taken to do that, because even that course of action can provide intelligence in providing a link to similar crime patterns going on throughout India.

Dr. Paul Smith

Dr. Paul Smith

Nic: I think forensics is underutilized in wildlife crime, and the more these methods are used, the awareness also increases deterrence from crime.

Paul: That is absolutely right. As soon as these poachers find out about the methods we use and advancements in forensics, they hesitate. I think a lot of these people carrying out these crimes are opportunists, they aren’t hardened criminals, and it might deter them from doing it.

Nic: But on the other side, offenders adapt too and are capable of becoming far more forensically aware as time goes on.

Developments in Forensics

Paul: When I started in forensics in 1998, you literally had to have a coin-sized quantity of blood to get any DNA. You can now get DNA even from dandruff, from a skin flake, from a minute sample. That is the degree of sensitivity of the technique.

Jac: It has been the biggest revolution, the progression in forensics.

Jac Reed

Jac Reed

Paul: The sensitivity, the science and the technology have changed. There’s bigger emphasis on mobile phones and the Internet, things connected to cyber space.

Jac: The other massive shift has been in anti-contamination methods. I think that’s the real change that’s happening now.

Challenges in Forensics

Jac: Like Paul mentioned before, what works in one place won’t work in another. With our work in Africa, they wanted their guys in and out of the crime scenes extremely quickly because of the dangers that are present; poachers attacking and killing them.

Paul: Another challenge I would like to mention is different jurisdictions, different law and different infrastructure. So, England, Wales, Northern Ireland, Scotland, USA, Australia, most of Europe and India have established a database, and legal frameworks but it has become evident that using forensic methods for wildlife crime is sometimes limited by laws or protocols. That’s going to be a challenge because as far as I understand it’s going to be difficult for rangers to link into the criminal database.

Nic: But also, to add to that, very remote areas where there’s no road access; somewhere like the Cairngorms National Park on top of the Cairngorms mountains in Scotland where we see Golden Eagles persecuted. You can’t take a lot of kit up to the top of a mountain range. Something that really stood out for me about the gel is the technique, was the fact that you can put it in your pocket.

Dr. Nicholas Pamment

Dr. Nicholas Pamment

Origin of Forensics

Paul: All forensic science means is the application of science and other methods to the law. The word forensic relates to latin for “for the forum” and it just simply means the relation of science to the law. In terms of the application of science in practice, you can go all the way to the Chinese where they use certain skills; to determine whether somebody was poisoned and that was also done in ancient Greece as well. I think it was in the mid 19th century, when scientist started looking into methods of identification by looking at anthropometry (measuring the length of limbs, the length of noses and proportions of the human body). They started looking at whether they could verify identification by the length of somebody’s nose or fingers. There was a whole host of real complex measurements that could be taken but it was so complicated and at that time finger marks were starting to be developed as a method. Scientists then started to look into the details, which further led them to cataloging it, after which the finger print method had been established for identification means. Due to how easy this method was, anthropometry was left behind.

Moving ahead, DNA recognition came in the 90s and since then we have seen the use of chemistry and physics to determine substances of the crime scenes. This next led to the developments of the microscope, so they could look closely at striation marks, tool marks on different surfaces, the impact of poison and injury on the body developed during this time. I think it took a really sharp turn, since the last century. In 1935, in the UK, we had the first forensic laboratory, which then became the Home Office forensic laboratory, then the forensic science service, but now we’ve got nothing. I think it was the 40s in the United States that national forensic labs started to form to support the police in what they do. Today you’ve got most countries in the world with a centralised forensic lab, which can do anything from marks and impressions, biological evidence, chemical evidence, toxicology, archeology, anthropology, you name it.

Forensic challenges India can have

Jac: Infrastructure would be one.

Nic: Political will as well. The impact that politicians can have in this area. And unless you get political buy in and political impetus behind an initiative, it doesn’t go anywhere.

Jac: Political will to actually implement the infrastructure.

Paul: Yes, India has the skill, India has the ability, India also has the knowledge, you’ve got intelligence and the people, but what I think is the issue not just in India but a number of countries is the style of working. People are not collaborating and talking to each other. Wildlife crime is a crime, it should be classed as a crime, and rangers should be empowered to have investigative powers to do their job.

Nic: Given the state we’re in with biodiversity loss, it should become high priority and it should have all the resources it needs.

Paul: I think that’s not the case just in India.

Nic: Yes, it’s certainly all over the world.

Future of Forensics

Paul: Forensics in the UK is at its darkest time and it can only get better. Because forensics in the UK has had countless reviews in the last couple of years, no answers are forthcoming because we’re caught in a perfect storm of demanding change, cutbacks, funding and lack of govt or centralised laboratories. The private sector in the area is crumbling under the weight of demand, so there is a perfect storm of things. So anything is better than what we have got going on now.

In terms of technology, in terms of what could be possible, some of Jac’s work on light sources for example looks ahead. It is exploring a virtual system, a non-destructive system of scanners and light sources that will go into a scene, built to detect key elements remotely. We may not have to throw powder everywhere, but manage with a little bit of gel, or a light source, to do the analysis at the scene. That’s where technology is taking us, which will be connected to intelligence systems, so we have real time exchange of information, from identifying an individual to finding them in the database; all this stuff leads to greater connectivity and that’s really how technology is telling us where we could go. But the infrastructures won’t allow us to get there.

Jac: What I hope for is the investigative mindset to come back, because it’s the simplicity, the ability to understand what is required to relate the scene to the investigation.

Nic: I think the more the resources get stretched and the lack of funds that we’re all encountering now, I think we will go back to basics and I also think that it’s so important that we don’t lose the basics.

Paul: That is absolutely spot on, because we are getting deskilled in this area and bringing that investigation awareness and knowledge back is vital. Forensic science for the largest part is about interpretation, and that goes back to the basic understanding of where it fits within that investigation. That is what the future should be. It is more skilled people working more on human factors, decision making within the forensic environment, for using the evidence better and not just the forensic people, the police, the criminal justice system, etc.

Nic: It’s so essential for wildlife crime to take all your knowledge up in your head.

About the course

Nic: I’ve just had one of our wildlife crime students who has done an amazing dissertation on “Antique Ivory sales on eBay”. She has done a fantastic piece of work where she’s identified suspicious Ivory sales over a 3-month period. It’s all been analyzed now and it truly is excellent work. Just like this we have students every year, in the wildlife crime cohort.

Paul: A couple of years ago I walked into the head quarter canteen at Hampshire Constabulary and I sat down to have a coffee, waiting to go into my meeting and I was suddenly approached by 17 students, who were a cohort of probation police officers, and say, “Paul Smith, oh my god thank you! We’re all police officers now, we’re probation officers, civilian investigators”. I was so pleased. A large amount of our students go into Hampshire Constabulary and fulfill their dream to be police officers.

Nic: I am really keen to see wildlife crime being taught in universities all over the world as part of criminal justice.

In order for forensic science to have a greater impact, universities must develop infrastructure to teach such courses, the professors said. Forensic experts within the field of forensics could also help popularise this science by liaising with one another, professors and organisations in similar and inter-disciplinary fields, they suggested. Bringing together technology, the legal system, the science, and the conservation aspect into forensics can help prepare the students for the future, the trio recommended.